The Jesuits as They Were

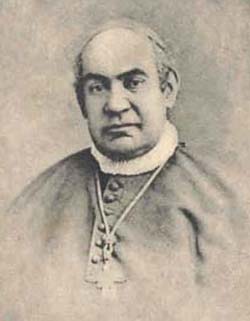

St. Anthony Mary Claret (b. 1807), whose feast day was yesterday, had originally wanted to become a Carthusian, but God had other plans; on his way to Rome to become a missionary, he stopped at a Jesuit house to make his yearly spiritual retreat--only to find himself a Jesuit novice by its end. "[I]t was all like a dream or a fantasy," he wrote. The only reason he had never considered becoming a Jesuit was, quite simply, because he did not feel worthy, so spectacularly did this order impress him. Although it would turn out later that it was not God's will that he remain in the order, he would always speak fondly of his time there.

St. Anthony Mary Claret (b. 1807), whose feast day was yesterday, had originally wanted to become a Carthusian, but God had other plans; on his way to Rome to become a missionary, he stopped at a Jesuit house to make his yearly spiritual retreat--only to find himself a Jesuit novice by its end. "[I]t was all like a dream or a fantasy," he wrote. The only reason he had never considered becoming a Jesuit was, quite simply, because he did not feel worthy, so spectacularly did this order impress him. Although it would turn out later that it was not God's will that he remain in the order, he would always speak fondly of his time there.Fr. Malachi Martin has already written a book tracking the rise and fall of this once-great community, responsible for so many glorious martyrdoms in Reformation England, for the spread of the gospel to the furthermost parts of every continent, and for the burgeoning of rigorous, orthodox seminaries and universities throughout the world. Since the 1960s, the order has largely given way to liberation theology, marked by instances of disobedience, such that it has, tragically, become something of a laughingstock among the orthodox Catholic community.

But none of this had yet touched the order of which Fr. Claret had become a part:

There were no mortifications ordered by the Rule. Yet in no other religious body, perhaps, is mortification practiced more assiduously than in the Society of Jesus. Some of the mortifications were exterior, others not so, but all had to have the permission of the director before practicing these acts. On Fridays, and nearly always on Saturdays, too, everybody fasted. Every Saturday night eggs and salad were passed to all, but no one would take the eggs. Desserts and dainty tidbits were taken very seldom. The religious of the house also left many other kinds of food untouched, and always those kinds which appealed more to the palate. I had observed that everyone ate very sparingly each day, and that the Fathers who were stouter and heavier than others were the very ones who ate the last. The spiritual director of the house ate bread every day of the week except Sunday, and drank only water. He used to kneel at a small table in the middle of the refectory and persevere in that position during all the dinner or supper of the community. How could anyone who looked at that venerable man, on his knees before a little table, eating his bread and sipping his water, refrain from feeling shame at the thought of sitting down and eating well-seasoned and dainty dishes?

Elswhere, Fr. Claret shows us why he was a saint (as an aside, his autobiography was written under obedience, though he preferred not to reveal things of his own life). Aboard a ship set for Rome, he spent the night sleeping on a pile of rope on deck, soaked by waves and by rain:

Elswhere, Fr. Claret shows us why he was a saint (as an aside, his autobiography was written under obedience, though he preferred not to reveal things of his own life). Aboard a ship set for Rome, he spent the night sleeping on a pile of rope on deck, soaked by waves and by rain:Next day, after the storm had subsided and the rain had disappeared, I took out my breviary and said the Office. Scarcely had I finished my prayers when an English gentleman came up to me and told me that he was a Catholic.... After speaking to me for a few moments, he went to his cabin, from which he emerged after a short time bringing in my direction a tray containing some gold coins.

...Gratefully I received it, and gave all the contributions to my poor fellow countrymen, so that not even one coin of all that money came to my possession, although it had been originally intended for me. I did not take even a mouthful of the food that was bought with the money, but contented myself with my own bread still soggy from the seawater. The Englishman knew that my Spanish friends were eating the food bought by the money which he had given me. He noticed, too, that I neither kept any money, nor partook of the food bought by it. This impressed him so favorably that he came to tell me...where he was going to stay, inviting me to go and see him at Rome, and assuring me that he would give me everything I needed.

This experience confirmed in me the conviction I had always entertained, which is: The best and most efficacious way to edify and move people is by way of example, by poverty, generosity, abstinence from food, by mortification and self-denial. This Englishman was surrounded by every possible luxury, having even his carriage with him in the boat, his servants, birds and dogs. From all this one would infer that my appearance would have excited in him anything but esteem. Yet on seeing a priest, poor, detached from worldly things, and mortified, it moved him in such a way that he did not know how to show his affection.

<< Home