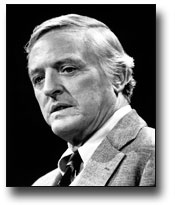

Joe Sobran, fired from National Review some years ago over differences in opinion,

wrote warmly of his old boss back in 2006:

In 1993 I pretty much defied William F. Buckley Jr., my boss at National Review for 21 years, to fire me, and he did. I was sorry it had to end that way, but things had become very strained between us. I’ve told my side of that story before.

What I’ve never told is what Bill was really like. And now that I want to, I hardly know where to start.

I just got the news that Bill has emphysema and has checked into the Mayo Clinic. At 80, he hasn’t looked well lately in his television appearances, so this shouldn’t have been a shock. But it’s a shock, all right — such a shock that I’m not really writing, I’m babbling.

Like millions of young conservatives in the 1960s, I adored Bill Buckley. I met him at my Michigan university in 1971, and a few months later he invited me to come to New York to write for him. I was thrilled, and on September 11, 1972, I went to work at National Review’s Manhattan office, a starstruck kid of 26. The biggest news story was still being called “the Watergate caper.”

What fun it was! In private Bill was every bit as witty as his public reputation, but warmer and funnier. He kept the office as happy as a nest of singing birds, with affectionate and gracious gestures for all of us. It pains me to recall how callow I was in those days, but he was always too encouraging to let me feel like anything but a prodigy.

He had help. Two of his sisters worked in the office too, Priscilla, his managing editor, and his kid sister Carole, whose desk was next to mine. They shared that Buckley radiance and humor. So, I learned, did all his siblings. Magic seemed to run in the family.

Bill had founded the magazine in 1955, and had gathered and fostered remarkable young writing talents: Garry Wills, John Leonard, Joan Didion, Arlene Croce, George Will, Richard Brookhiser, Paul Gigot, and many others were among his discoveries. He’d also attracted such notable older conservative intellectuals as James Burnham, Willmoore Kendall, Russell Kirk, Frank Meyer, and Richard Weaver. These brilliant, headstrong people sometimes had sharp differences among themselves, but Bill’s genially magnetic personality usually kept the peace.

Over the years I came to know another side of Bill. When I had serious troubles, he was a generous friend who did everything he could to help me without being asked. And I wasn’t the only one. I gradually learned of many others he’d quietly rescued from adversity. He’d supported a once-noted libertarian in his destitute old age, when others had forgotten him. He’d helped two pals of mine out of financial difficulties. And on and on. Everyone seemed to have a story of Bill’s solicitude. When you told your own story to a friend, you’d hear one from him. It was as if we were all Bill Buckley’s children.

It went far beyond sharing his money. One of Bill’s best friends was Hugh Kenner, the great critic who died two years ago. Hugh was hard of hearing, and once, after a 1964 dinner with Hugh and Charlie Chaplin, Bill scolded Hugh for being too stubborn to use a hearing aid. Here were the greatest comedian of the age and the greatest student of comedy, and Hugh had missed much of the conversation! Later Hugh’s wife told me how grateful Hugh had been for that scolding. Nobody else would have dared speak to her husband that way. Only a true friend would. If Bill saw you needed a little hard truth, he’d tell you, even if it pained him to say it.

I once spent a long evening with one of Bill’s old friends from Yale, whose name I won’t mention. He told me movingly how Bill stayed with him to comfort him when his little girl died of brain cancer. If Bill was your friend, he’d share your suffering when others just couldn’t bear to. What a great heart — eager to spread joy, and ready to share grief!

Compared with all this, the political differences that finally drove us apart seem trivial now. I saw the same graciousness in his relations with everyone from presidents to menials. I learned a lot of things from Bill Buckley, but the best thing he taught me was how to be a Christian. May Jesus comfort him now.

And

Justin Raimondo over at Taki's Top Drawer discusses Buckley's legacy:

It is hard to over-emphasize the importance of National Review for the young conservatives of the 1960s: there was no other magazine, no other center of intellectual nourishment, for us, but then none was needed. NR was quite enough. That’s because there was no party line, no neoconservative enforcers of the Frummian variety, no partisan sensibility that distorted the editors’ always sharp analysis of what we, as conservatives, ought to do, say, and think about this or that, no looking over one’s shoulder. In the pages of NR the intellectual heavyweights—Meyer, Russell Kirk, and the like—battled it out: Liberty versus Order, Fusionism versus Traditionalism, Rollback versus Containment. The Big Issues, and all very appealing to a callow youth in search of answers and intellectual adventure. And not all politics all the time, either, but columns on the arts, on travel, on matters great and small that revealed a much wider world than the suburban desert in which I lived, that gave me a hint at what life had to offer if only I kept up by subscription to NR—and a dictionary by my side.

Joe Sobran, fired from National Review some years ago over differences in opinion, wrote warmly of his old boss back in 2006:

Joe Sobran, fired from National Review some years ago over differences in opinion, wrote warmly of his old boss back in 2006: And Justin Raimondo over at Taki's Top Drawer discusses Buckley's legacy:

And Justin Raimondo over at Taki's Top Drawer discusses Buckley's legacy:

<< Home