Julie London sings

"Cry Me a River." (Personally, I think

Helen Merrill rivals her voice, as does, on some tunes, Doris Day, featured

here singing "I Love Paris.")

Not particularly sultry, but with a unique, lovely, almost childlike voice, a favorite of mine has always been Astrud Gilberto. Here's her take on

Corcovado with Stan Getz.

With all these posts on jazz, one might think I was raised on the genre, when in fact I was trained in classical piano. My lessons began at age five (which I've been told by those in the know is far too late a beginning for anyone with professional aspirations, some of which I fancied in my adolescence). After years of lessons and nervewracking performances, I came to study under concert pianist

Boaz Sharon. He was a short, softspoken, intelligent man, and a consummate perfectionist. I had fast fingers, but Sharon was the first to painstakingly work on my control. I remember spending an entire semester trying to get through Chopin's Etude 25, No. 1 ('"Aeolian Harp"). If you know anything about the Harp Etude, then you know that it has about a thousand notes, all to be played in rapid succession so that the final product sounds like, well, a harp.

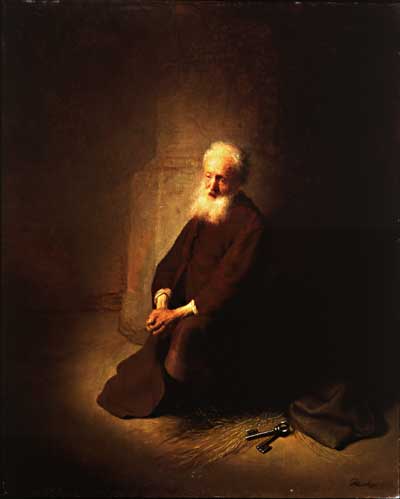

Arthur Rubinstein gives a command performance here.An enlarged sample of the first bar is shown above. Together with the scales, arpeggios, octaves, chromatics, fugues, and other pieces assigned, each week I had to sit before Boaz and play the Harp Etude without missing a single one of those thousand notes. If I missed just one, I had to start all over again. Naturally, because my fingers were fast and tended to get away from me, I was forced to slow down--and there was nothing in the world more difficult for me than to play the Harp Etude

slowly. Week after week after week of playing the piece, making errors, starting all over again, making more errors, starting over again, making mistakes once more, starting over again, etc. was quite an experience. Like any good teacher, he remained patient throughout. Lo and behold, on the very last day of class, I finally played the entire piece through without making a single mistake. I was rather proud of myself--but when he asked me to stay on for further studies (even guaranteeing me an A the next term), I refused. He asked me again, and I refused. Once more, and I still refused. Oh, it remains one of the most foolish and regrettable decisions I've ever made--but in my youth I lacked the discipline and drive to put in the hours of practice required each day. I had a love/hate relationship with the piano--and by the end of that semester, I was leaning more towards the latter.

Over a decade later, my fingers have sadly fallen into disuse, and I no longer have access to a piano. But it's an art I plan to resume once we buy our own instrument, and an art I plan to pass onto my daughter--even if I can never return to those younger days when I could play the Harp Etude flawlessly.

Following on an

Following on an